THE BIG IDEA:

One in five voters in 2012 were college-educated white women. Mitt Romney won

them by six points, according to exit polls.

Our fresh

Washington Post-ABC News Tracking Poll, which has Hillary Clinton ahead by just

two points among all likely voters nationally, finds that Donald Trump is

losing college-educated white women by 27 points.

If the

Republican nominee were anywhere close to Romney’s 52 percent support level

among this traditionally Republican-leaning constituency, he would likely win

the election. But drilling into the crosstabs of our polling and reviewing

credible, state-level data demonstrate how highly unlikely it is that this

constituency will waver in the final days. It is one of the reasons that, even

though the race has tightened pretty dramatically, Clinton retains a significant

structural advantage.

If the

Republican nominee were anywhere close to Romney’s 52 percent support level

among this traditionally Republican-leaning constituency, he would likely win

the election. But drilling into the crosstabs of our polling and reviewing

credible, state-level data demonstrate how highly unlikely it is that this

constituency will waver in the final days. It is one of the reasons that, even

though the race has tightened pretty dramatically, Clinton retains a significant

structural advantage.

The gender gap

is nothing new. Democrats tend to perform exceptionally well with unmarried and

minority women. A Pew study in July found that there was no difference in

candidate support between men and women in 1972 and 1976, but since 1980 women

writ large have preferred Democratic presidential candidates by an average of

eight points.

Our national

tracking polling shows that the race has moved back toward something close to

this historic norm. Men prefer Trump by 11 points (51-40) and women prefer

Clinton by 11 points (52-41).

Clinton is

ahead only 11 points among women overall because Trump is running up his margin

among white women without college degrees. They favor him by 28 points, 61

percent to 33 percent, despite the dozen women who have now come forward

publicly to accuse him of sexual misconduct.

But the

preference for Clinton among college-educated, white women matters a great deal

because they habitually turn out to vote at higher rates than almost every

other group of voters, including less-educated women. So, in an election with

lagging enthusiasm, this constituency packs a bigger punch.

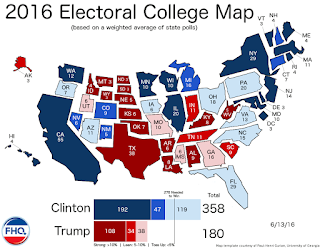

Donald Trump is

busy building his Cabinet and planning his agenda, but he isn't really,

officially going to be President quite yet. One of the peculiarities of

American democracy is that it's actually a group of 538 "electors" --

members of the Electoral College -- in this nation of 318 million who actually

pick the president.

Donald Trump is

busy building his Cabinet and planning his agenda, but he isn't really,

officially going to be President quite yet. One of the peculiarities of

American democracy is that it's actually a group of 538 "electors" --

members of the Electoral College -- in this nation of 318 million who actually

pick the president.